There’s a quotation that I like to share with the students in my writing classes. It’s fairly recent, by J. Patrick Lewis, who is a children’s book author and former United States children’s poet laureate. In a few sentences, Lewis encapsulates what reflection is all about: doing it better.

If you say you want to be a writer . . . I applaud you. The next words out of your mouth should be, “But I promise to be a rewriter!” I don’t even know why we use the word “writer.” All the great writers in the world have been rewriters. So buy yourself a big wastebasket, and keep it filled.

Like Lewis, we all have big wastebaskets that we fill, and into which we toss in personal or professional mistakes or adjustments. We assess the merits of a new restaurant, the benefits of traveling to Florida in January, or the results of our latest half-marathon. They key point is that we ask ourselves, “What will I do next?” and “What can I do better?”

But unlike Lewis, I’d say that students shouldn’t throw the ideas away. Instead, use them to build something new. Let’s think of that wastebasket as a recycle bin. Reflection is about the learning process. While the word tends to be overused in education, some scholars claim that regular reflective journaling in education can be “transformational,” because it allows students to evaluate their previous work, record where the problems occurred, and then alter their attitudes, actions, and behaviors.

There is no single way to build reflection into the classroom; it might be an informal discussion or a formal written assignment. In a classroom where instructors engage in scaffolding—incremental lessons that move students toward greater understanding of concepts—reflective questions and writing can appear at any point in the process. In addition, the questions can be applied to any discipline.

For example, set up a reflection about prior knowledge before a new unit. Ask whether students have any assumptions or preconceptions about the upcoming activity. Afterwards, they may consider whether any problems or conflicts were identified through the session—and how those related back to their assumptions. I often do this when approaching a new novel or set of poems in my literature courses; we judge the book by its cover (as well as its publication date and location). And since self-disclosure can be risky in open discussion, the students will write down their preconceptions on notecards. On the other hand, rather than a meta-cognitive activity structured around an academic question, some instructors elicit the personal feelings that might not otherwise be evident in the assignment: What do you predict? What are your feelings (hesitant? excited?)? What was good or bad about the experience?

Instructors working with Quest III students who are undertaking community engagement projects have found that reflection is essential at all stages of the process. Students may have unrealistic expectations about how smoothly their volunteer experiences will unfold, and these expectations are born of inexperience. Thus, eliciting pre-conceptions about how they envision their role and the people with whom they will work should help them articulate, recall, and compare their actual experiences to their initial vision. The time spent on reflection will also help the students build narratives that can be used during job interviews, so the students will see the benefits beyond the classroom.

Some of the questions that we have used with students at the end of the community workday also ask them to predict connections to their future selves:

- What are some new experiences, ideas, or facts that you learned today? How will you be able to use these in the future?

- Do you believe that your actions had any impact in the community?

- What problems or conflicts were identified through the session today? Were the problems social, environmental, or economic? What other factors were involved (such as laws, technology, and communication)? What are some possible solutions to the conflict? How does that solution affect different populations? Will they all be happy with the outcome?

- From something that you learned today, express a contrasting perspective. Think about something that wasn’t mentioned or look at the issue from another viewpoint. Here are the lenses that you’ll be asked to use in USP Connect (English 300):

- Economy

- Society, including populations and social institutions

- Environment

- Culture, including arts, music, and humanities

- Technology

- Information and communication

- Government and laws

- How have you challenged yourself to see things from new perspectives?

In the Department of English, we’ve recently added five questions for reflection into the first formal assignment for English 300 / Advanced Writing, Connect. The answers to these questions will be typed and turned in with the written assignment. These questions appear originally in an extensive document on reflection published by Edutopia, the George Lucas Educational Foundation.

- How much did you know about this subject before you started?

- Have you changed any ideas that you used to have about the subject?

- Which of your resources was especially helpful to answering your questions?

- What does this project reveal about you as a learner?

- Do you have any new goals, either for your education or for your writing?

(For many more useful questions, view the full document at: https://www.edutopia.org/pdfs/stw/edutopia-stw-replicatingPBL-21stCAcad-reflection-questions.pdf.)

With all these questions, it’s especially important that the reflection session builds a bridge between previous knowledge and the ways that students will challenge themselves o in the future. Application–“What will I do next?”–is as important as important as assessment.

Process is often ephemeral. When we learn to do something, we often forget the steps we took to get to the point of fluency. Practically, I’ve been turning to GoogleDocs as a means for students to write, revise, revisit, share, and save reflective pieces, because the work will stay with them for several semesters and therefore across several courses and resumes, rather than being lost on a flash drive.

Allowing time for reflection in the university classroom not only gives students time to fill their recycle bins, but also provides them with creative, self-directed time to rummage through the bins and produce something new. So I ask you: What will you do next?

– Marguerite Helmers is Professor of English and Director of Advanced Writing / Connect. She teaches expository writing and British and Irish literature, and has led two study tours to Ireland with Quest III students.

participate in Academic Open House Week. Many departments have thought a lot about what that open house would look like. Others are still planning.

participate in Academic Open House Week. Many departments have thought a lot about what that open house would look like. Others are still planning. I was flabbergasted by all these good ideas. I can’t wait to visit as many open houses as I can squeeze in. Invite your majors and minors. Let’s get out there and celebrate our academic opportunities!

I was flabbergasted by all these good ideas. I can’t wait to visit as many open houses as I can squeeze in. Invite your majors and minors. Let’s get out there and celebrate our academic opportunities!

scholarship that more advanced undergraduates are doing here.

scholarship that more advanced undergraduates are doing here. Several years ago, I remember discussing the idea of “paired courses” as the university embarked on developing the University Studies Program. The idea was that the Communication Studies 111 course I teach would be paired with another Quest 1 course from another department like Women’s Studies, History, Political Science, Anthropology, etc. Faculty and staff were asked to meet the instructor teaching the paired course and share syllabi, assignments, and their vision for the course. At the time I thought, “How will this work?” My colleagues and I sometimes teach four to five sections of public speaking in any given semester. When will we find time to collaborate?”

Several years ago, I remember discussing the idea of “paired courses” as the university embarked on developing the University Studies Program. The idea was that the Communication Studies 111 course I teach would be paired with another Quest 1 course from another department like Women’s Studies, History, Political Science, Anthropology, etc. Faculty and staff were asked to meet the instructor teaching the paired course and share syllabi, assignments, and their vision for the course. At the time I thought, “How will this work?” My colleagues and I sometimes teach four to five sections of public speaking in any given semester. When will we find time to collaborate?”

Next, we’re thinking about how Emmet’s students might benefit from what Angela and I teach in our communication courses. Certainly, his students can learn more about perception by studying the topic from a Communication Studies perspective.

Next, we’re thinking about how Emmet’s students might benefit from what Angela and I teach in our communication courses. Certainly, his students can learn more about perception by studying the topic from a Communication Studies perspective.

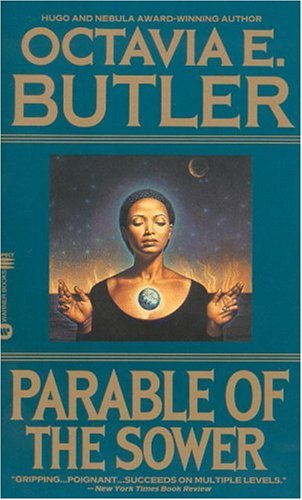

Butler’s dystopian vision provides us with the reason that the USP’s emphasis on intercultural knowledge and competence is so important. It provides students with the skills, abilities and attitudes essential to the healthy functioning of our democracy. With it, students will be able to communicate across differences and value multiple perspectives. These capabilities are essential to collaborative problem-solving. Moreover, they are abilities that have the potential to ensure just, fair and peaceful solutions to conflicts currently facing our nation.

Butler’s dystopian vision provides us with the reason that the USP’s emphasis on intercultural knowledge and competence is so important. It provides students with the skills, abilities and attitudes essential to the healthy functioning of our democracy. With it, students will be able to communicate across differences and value multiple perspectives. These capabilities are essential to collaborative problem-solving. Moreover, they are abilities that have the potential to ensure just, fair and peaceful solutions to conflicts currently facing our nation.